Alagille Syndrome

What is Alagille syndrome?

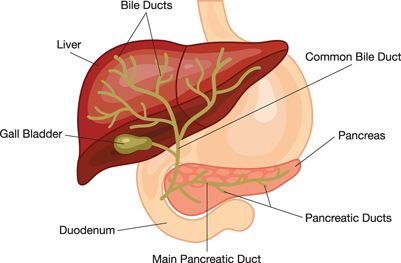

Alagille syndrome is a genetic condition that results in various symptoms in different parts of the body, including the liver. A person with Alagille syndrome has fewer than the normal number of small bile ducts inside the liver. The liver is the organ in the abdomen—the area between the chest and hips—that makes blood proteins and bile, stores energy and nutrients, fights infection, and removes harmful chemicals from the blood.

Bile ducts are tubes that carry bile from the liver cells to the gallbladder for storage and to the small intestine for use in digestion. Bile is fluid made by the liver that carries toxins and waste products out of the body and helps the body digest fats and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K. In people with Alagille syndrome, the decreased number of bile ducts causes bile to build up in the liver, a condition also called cholestasis, leading to liver damage and liver disease.

[Top]

What is the digestive system?

The digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract—also called the digestive tract—and the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder. The GI tract is a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus. The hollow organs that make up the GI tract are the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine—which includes the colon and rectum—and anus. Food enters the mouth and passes to the anus through the hollow organs of the digestive system. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are the solid organs of the digestive system. The digestive system helps the body digest food.

[Top]

What causes Alagille syndrome?

Alagille syndrome is caused by a gene mutation, or defect. Genes provide instructions for making proteins in the body. A gene mutation is a permanent change in the DNA sequence that makes up a gene. DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is the material inside cells that carries genetic information and passes genes from parent to child. Approximately 30 to 50 percent of people with Alagille syndrome have an inherited gene mutation, meaning it has been passed on by a parent. In the remaining cases, the gene mutation develops spontaneously.1 In spontaneous cases, neither parent carries a copy of the mutated gene.

Most cases of Alagille syndrome are caused by a mutation in the JAGGED1 (JAG1) gene. In less than 1 percent of cases, a mutation in the NOTCH2 gene is the cause.2

1Spinner NB, Leonard LD, Krantz ID. Alagille syndrome. GeneReviews website. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1273/External NIH Link. Updated February 28, 2013. Accessed July 16, 2014.

2Kamath BM, Bauer RC, Loomes KM, et al. NOTCH2 mutations in Alagille syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2012;49(2):138–144.

[Top]

Genetic Disorders

Each cell contains thousands of genes that provide the instructions for making proteins for growth and repair of the body. If a gene has a mutation, the protein made by that gene may not function properly, which sometimes creates a genetic disorder. Not all gene mutations cause a disorder.

People have two copies of most genes; one copy is inherited from each parent. A genetic disorder occurs when one or both parents pass a mutated gene to a child at conception. A genetic disorder can also occur through a spontaneous gene mutation, meaning neither parent carries a copy of the mutated gene. Once a spontaneous gene mutation has occurred in a person, it can be passed to the person's children.

Read more about genes and genetic conditions at the U.S. National Library of Medicine's (NLM's) Genetics Home Reference at www.ghr.nlm.nih.govExternal NIH Link.

[Top]

How common is Alagille syndrome and who is more likely to have Alagille syndrome?

Alagille syndrome occurs in about one of every 30,000 live births.3 The disorder affects both sexes equally and shows no geographical, racial, or ethnic preferences.

JAG1 and NOTCH2 gene mutations are inherited in an autosomal dominant way, which means a child can get Alagille syndrome by inheriting either of the gene mutations from only one parent. Each child of a parent with an autosomal dominant mutation has a 50 percent chance of inheriting the mutated gene.

The following chart shows the chance of inheriting an autosomal dominant gene mutation:

The gene mutations that cause Alagille syndrome may cause mild or subtle symptoms. Some people may not know they are affected, while others with the gene mutation may develop more serious characteristics of Alagille syndrome. A person with a gene mutation, whether showing serious symptoms or not, has Alagille syndrome and can pass the gene mutation to a child.

Read more about how genetic conditions are inherited at the NLM's Genetics Home Reference website at www.ghr.nlm.nih.govExternal NIH Link.

3Kamath BM, Loomes KM, Piccoli DA. Medical management of Alagille syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition.2010;50(6):580–586.

[Top]

What are the signs and symptoms of Alagille syndrome?

The signs and symptoms of Alagille syndrome and their severity vary, even among people in the same family sharing the same gene mutation.

Liver

In some people, problems in the liver may be the first signs and symptoms of the disorder. These signs and symptoms can occur in children and adults with Alagille syndrome, and in infants as early as the first 3 months of life.

Jaundice. Jaundice—when the skin and whites of the eyes turn yellow—is a result of the liver not removing bilirubin from the blood. Bilirubin is a reddish-yellow substance formed when hemoglobin breaks down. Hemoglobin is an iron-rich protein that gives blood its red color. Bilirubin is absorbed by the liver, processed, and released into bile. Blockage of the bile ducts forces bilirubin and other elements of bile to build up in the blood.

Jaundice may be difficult for parents and even health care providers to detect. Many healthy newborns have mild jaundice during the first 1 to 2 weeks of life due to an immature liver. This normal type of jaundice disappears by the second or third week of life, whereas the jaundice of Alagille syndrome deepens. Newborns with jaundice after 2 weeks of life should be seen by a health care provider to check for a possible liver problem.

Dark urine and gray or white stools. High levels of bilirubin in the blood that pass into the urine can make the urine darker, while stool lightens from a lack of bilirubin reaching the intestines. Gray or white bowel movements after 2 weeks of age are a reliable sign of a liver problem and should prompt a visit to a health care provider.

Pruritus. The buildup of bilirubin in the blood may cause itching, also called pruritus. Pruritus usually starts after 3 months of age and can be severe.

Xanthomas. Xanthomas are fatty deposits that appear as yellow bumps on the skin. They are caused by abnormally high cholesterol levels in the blood, common in people with liver disease. Xanthomas may appear anywhere on the body. However, xanthomas are usually found on the elbows, joints, tendons, knees, hands, feet, or buttocks.

Other Signs and Symptoms of Alagille Syndrome

Certain signs of Alagille syndrome are unique to the disorder, including those that affect the vertebrae and facial features.

Face. Many children with Alagille syndrome have deep-set eyes, a straight nose, a small and pointed chin, large ears, and a prominent, wide forehead. These features are not usually recognized until after infancy. By adulthood, the chin is more prominent.

Eyes. Posterior embryotoxon is a condition in which an opaque ring is present in the cornea, the transparent covering of the eyeball. The abnormality is common in people with Alagille syndrome, though it usually does not affect vision.

Skeleton. The most common skeletal defect in a person with Alagille syndrome is when the shape of the vertebrae—bones of the spine—gives the appearance of flying butterflies. This defect, known as "butterfly" vertebrae, rarely causes medical problems or requires treatment.

Heart and blood vessels. People with Alagille syndrome may have the following signs and symptoms having to do with the heart and blood vessels:

- heart murmur—an extra or unusual sound heard during a heartbeat. A heart murmur is the most common sign of Alagille syndrome other than the general symptoms of liver disease.1 Most people with Alagille syndrome have a narrowing of the blood vessels that carry blood from the heart to the lungs.1 This narrowing causes a murmur that can be heard with a stethoscope. Heart murmurs usually do not cause problems.

- heart walls and valve problems. A small number of people with Alagille syndrome have serious problems with the walls or valves of the heart. These conditions may need treatment with medications or corrective surgery.

- blood vessel problems. People with Alagille syndrome may have abnormalities of the blood vessels in the head and neck. This serious complication can lead to internal bleeding or stroke. Alagille syndrome can also cause narrowing or bulging of other blood vessels in the body.

Kidney disease. A wide range of kidney diseases can occur in Alagille syndrome. The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs, each about the size of a fist, that filter wastes and extra fluid from the blood. Some people have small kidneys or have cysts—fluid-filled sacs—in the kidneys. Kidney function can also decrease.

[Top]

What are the complications of Alagille syndrome?

The complications of Alagille syndrome include liver failure, portal hypertension, and growth problems. People with Alagille syndrome usually have a combination of complications, and may not have every complication listed below.

Liver failure. Over time, the decreased number of bile ducts may lead to chronic liver failure, also called end-stage liver disease. This condition progresses over months, years, or even decades. The liver can no longer perform important functions or effectively replace damaged cells. A person may need a liver transplant. A liver transplant is surgery to remove a diseased or an injured liver and replace it with a healthy whole liver or a segment of a liver from another person, called a donor.

Portal hypertension. The spleen is the organ that cleans blood and makes white blood cells. White blood cells attack bacteria and other foreign cells. Blood flow from the spleen drains directly into the liver. When a person with Alagille syndrome has advanced liver disease, the blood flow backs up into the spleen and other blood vessels. This condition is called portal hypertension. The spleen may become larger in the later stages of liver disease. A person with an enlarged spleen should avoid contact sports to protect the organ from injury. Advanced portal hypertension can lead to serious bleeding problems.

Growth problems. Alagille syndrome can lead to poor growth in infants and children, as well as delayed puberty in older children. Liver disease can cause malabsorption, which can result in growth problems. Malabsorption is the inability of the small intestine to absorb nutrients from foods, which results in protein, calorie, and vitamin deficiencies. Serious heart problems, if present in Alagille syndrome, can also affect growth.

Malabsorption. People with Alagille syndrome may have diarrhea—loose, watery stools—due to malabsorption. The condition occurs because bile is necessary for the digestion of food. Malabsorption can lead to bone fractures, eye problems, blood-clotting problems, and learning delays.

Long-term Outlook

The long-term outlook for people with Alagille syndrome depends on several factors, including the severity of liver damage and heart problems. Predicting who will experience improved bile flow and who will progress to chronic liver failure is difficult. Ten to 30 percent of people with Alagille syndrome will eventually need a liver transplant.3

Many adults with Alagille syndrome whose symptoms improve with treatment lead normal, productive lives. Deaths in people with Alagille syndrome are most often caused by chronic liver failure, heart problems, and blood vessel problems.

[Top]

How is Alagille syndrome diagnosed?

A health care provider diagnoses Alagille syndrome by performing a thorough physical exam and ordering one or more of the following tests and exams:

- blood test

- urinalysis

- x ray

- abdominal ultrasound

- cardiology exam

- slit-lamp exam

- liver biopsy

- genetic testing

Alagille syndrome can be difficult to diagnose because the signs and symptoms vary and the syndrome is so rare.

For a diagnosis of Alagille syndrome, three of the following symptoms typically should be present:

- liver symptoms, such as jaundice, pruritus, malabsorption, and xanthomas

- heart abnormalities or murmurs

- skeletal abnormalities

- posterior embryotoxon

- facial features typical of Alagille syndrome

- kidney disease

- blood vessel problems

A health care provider may perform a liver biopsy to diagnose Alagille syndrome; however, it is not necessary to make a diagnosis. A diagnosis can be made in a person who does not meet the clinical criteria of Alagille syndrome yet does have a gene mutation of JAG1. The health care provider may have a blood sample tested to look for the JAG1 gene mutation. The gene mutation can be identified in 94 percent of people with a diagnosis of Alagille syndrome.2

Blood test. A blood test involves drawing blood at a health care provider's office or a commercial facility and sending the sample to a lab for analysis. The blood test can show nutritional status and the presence of liver disease and kidney function.

Urinalysis. Urinalysis is the testing of a urine sample. The urine sample is collected in a special container in a health care provider's office or a commercial facility and can be tested in the same location or sent to a lab for analysis. Urinalysis can show many problems of the urinary tract and other body systems. The sample may be observed for color, cloudiness, or concentration; signs of drug use; chemical composition, including glucose; the presence of protein, blood cells, or bacteria; or other signs of disease.

X ray. An x ray is a picture created by using radiation and recorded on film or on a computer. The amount of radiation used is small. An x-ray technician performs the x ray at a hospital or an outpatient center, and a radiologist—a doctor who specializes in medical imaging—interprets the images. Anesthesia is not needed. The patient will lie on a table or stand during the x ray. The technician positions the x-ray machine over the spine area to look for "butterfly" vertebrae. The patient will hold his or her breath as the picture is taken so that the picture will not be blurry. The patient may be asked to change position for additional pictures.

Abdominal ultrasound. Ultrasound uses a device, called a transducer, that bounces safe, painless sound waves off organs to create an image of their structure. The transducer can be moved to different angles to make it possible to examine different organs. In abdominal ultrasound, the health care provider applies a gel to the patient's abdomen and moves a handheld transducer over the skin. The gel allows the transducer to glide easily, and it improves the transmission of the signals. A specially trained technician performs the procedure in a health care provider's office, an outpatient center, or a hospital, and a radiologist interprets the images; anesthesia is not needed. The images can show an enlarged liver or rule out other conditions.

Cardiology exam. A cardiologist—a doctor who treats people who have heart problems—performs a cardiology exam in a health care provider's office, an outpatient center, or a hospital. During a full exam, a cardiologist may inspect the patient's physical appearance, measure pulse rate and blood pressure, observe the jugular vein, check for rapid or skipped heartbeats, listen for variations in heart sounds, and listen to the lungs.

Slit-lamp exam. An ophthalmologist—a doctor who diagnoses and treats all eye diseases and eye disorders—performs a slit-lamp exam to diagnose posterior embryotoxon. The ophthalmologist examines the eye with a slit lamp, a microscope combined with a high-intensity light that shines a thin beam on the eye. While sitting in a chair, the patient will rest his or her head on the slit lamp. A yellow dye may be used to examine the cornea and tear layer. The dye is applied as a drop, or the specialist may touch a strip of paper stained with the dye to the white of the patient's eye. The specialist will also use drops in the patient's eye to dilate the pupil.

Liver biopsy. A liver biopsy is a procedure that involves taking a piece of liver tissue for examination with a microscope for signs of damage or disease. The health care provider may ask the patient to stop taking certain medications temporarily before the liver biopsy. The patient may be asked to fast for 8 hours before the procedure.

During the procedure, the patient lies on a table, right hand resting above the head. A local anesthetic is applied to the area where the biopsy needle will be inserted. If needed, sedatives and pain medication are also given. The health care provider uses a needle to take a small piece of liver tissue. The health care provider may use ultrasound, computerized tomography scans, or other imaging techniques to guide the needle. After the biopsy, the patient should lie on the right side for up to 2 hours and is monitored an additional 2 to 4 hours before being sent home.

Genetic testing. The health care provider may refer a person suspected of having Alagille syndrome to a geneticist—a doctor who specializes in genetic disorders. For a genetic test, the geneticist takes a blood or saliva sample and analyzes the DNA for the JAG1 gene mutation. The geneticist tests for the JAG1 gene mutation first, since it is more common in Alagille syndrome than NOTCH2. Genetic testing is often done only by specialized labs. The results may not be available for several months because of the complexity of the testing.

The usefulness of genetic testing for Alagille syndrome is limited by two factors:

- Detection of a mutated gene cannot predict the onset of symptoms or how serious the disorder will be.

- Even if a mutated gene is found, no specific cure for the disorder exists.

[Top]

When to Consider Genetic Counseling

People who are considering genetic testing may want to consult a genetics counselor. Genetic counseling can help family members understand how test results may affect them individually and as a family. Genetic counseling is provided by genetics professionals—health care professionals with specialized degrees and experience in medical genetics and counseling. Genetics professionals include geneticists, genetics counselors, and genetics nurses.

Genetics professionals work as members of health care teams, providing information and support to individuals or families who have genetic disorders or a higher chance of having an inherited condition. Genetics professionals

- assess the likelihood of a genetic disorder by researching a family's history, evaluating medical records, and conducting a physical exam of the patient and other family members

- weigh the medical, social, and ethical decisions surrounding genetic testing

- provide support and information to help a person make a decision about testing

- interpret the results of genetic tests and medical data

- provide counseling or refer individuals and families to support services

- serve as patient advocates

- explain possible treatments or preventive measures

- discuss reproductive options

Genetic counseling may be useful when a family member is deciding whether to have genetic testing and again later when test results are available.

[Top]

How is Alagille syndrome treated?

Treatment for Alagille syndrome includes medications and therapies that increase the flow of bile from the liver, promote growth and development in infants' and children's bodies, correct nutritional deficiencies, and reduce the person's discomfort. Ursodiol (Actigall, Urso) is a medication that increases bile flow. Other treatments address specific symptoms of the disorder.

Liver failure. People with Alagille syndrome who develop end-stage liver failure need a liver transplant with a whole liver from a deceased donor or a segment of a liver from a living donor. People with Alagille syndrome who also have heart problems may not be candidates for a transplant because they could be more likely to have complications during and after the procedure. A liver transplant surgical team performs the transplant in a hospital.

More information is provided in the NIDDK health topic, Liver Transplantation.

Pruritus. Itching may decrease when the flow of bile from the liver is increased. Medications such as cholestyramine (Prevalite), rifampin (Rifadin, Rimactane), naltrexone (Vivitrol), or antihistamines may be prescribed to relieve pruritus. People should hydrate their skin with moisturizers and keep their fingernails trimmed to prevent skin damage from scratching. People with Alagille syndrome should avoid baths and take short showers to prevent the skin from drying out.

If severe pruritus does not improve with medication, a procedure called partial external biliary diversion may provide relief from itching. The procedure involves surgery to connect one end of the small intestine to the gallbladder and the other end to an opening in the abdomen—called a stoma—through which bile leaves the body and is collected in a pouch. A surgeon performs partial external biliary diversion in a hospital. The patient will need general anesthesia.

Malabsorption and growth problems. Infants with Alagille syndrome are given a special formula that helps the small intestine absorb much-needed fat. Infants, children, and adults can benefit from a high-calorie diet, calcium, and vitamins A, D, E, and K. They may also need additional zinc. If someone with Alagille syndrome does not tolerate oral doses of vitamins, a health care provider may give the person injections for a period of time. A child may receive additional calories through a tiny tube that is passed through the nose into the stomach. If extra calories are needed for a long time, a health care provider may place a tube, called a gastrostomy tube, directly into the stomach through a small opening made in the abdomen. A child's growth may improve with increased nutrition and flow of bile from the liver.

Xanthomas. For someone who has Alagille syndrome, these fatty deposits typically worsen over the first few years of life and then improve over time. They may eventually disappear in response to partial external biliary diversion or the medications used to increase bile flow.

[Top]

Can Alagille syndrome be prevented?

Scientists have not yet found a way to prevent Alagille syndrome. However, complications of the disorder can be managed with the help of health care providers. Routine visits with a health care team are needed to prevent complications from becoming worse.

[Top]

Eating, Diet, and Nutrition

Researchers have not found that eating, diet, and nutrition play a role in causing or preventing Alagille syndrome. However, these factors are important for people with Alagille syndrome, particularly children, who are malnourished, growing poorly, or have delayed puberty. Caregivers and parents of children with Alagille syndrome should try to maximize their children's potential for growth through good eating, diet, and nutrition.

A nutritionist or a dietitian—a person with training in nutrition and diet—can work with someone with Alagille syndrome and his or her health care team to build an appropriate healthy eating plan. A person with Alagille syndrome may need to take dietary supplements or vitamins in addition to eating a set number of calories, based on the type of complications the person has. Researchers consider good nutrition to be one of the most important aspects of managing the disorder.

If potential liver problems are present, a person with Alagille syndrome should not drink alcoholic beverages without talking with his or her health care provider first.

Additionally, eating, diet, and nutrition play a part in overall health and preventing further health problems.

[Top]

Points to Remember

- Alagille syndrome is a genetic condition that results in various symptoms in different parts of the body, including the liver.

- A person with Alagille syndrome has fewer than the normal number of small bile ducts inside the liver.

- In people with Alagille syndrome, the decreased number of bile ducts causes bile to build up in the liver, a condition also called cholestasis, leading to liver damage and liver disease.

- Alagille syndrome is caused by a gene mutation, or defect. Approximately 30 to 50 percent of people with Alagille syndrome have an inherited gene mutation, meaning it has been passed on by a parent.

- Alagille syndrome occurs in about one of every 30,000 live births. The disorder affects both sexes equally and shows no geographical, racial, or ethnic preferences.

- The gene mutations that cause Alagille syndrome may cause mild or subtle symptoms. Some people may not know they are affected.

- The signs and symptoms of Alagille syndrome and their severity vary, even among people in the same family sharing the same gene mutation.

- In some people, problems in the liver may be the first signs and symptoms of the disorder.

- The complications of Alagille syndrome include liver failure, portal hypertension, and growth problems.

- Ten to 30 percent of people with Alagille syndrome will eventually need a liver transplant.

- A health care provider diagnoses Alagille syndrome by performing a thorough physical exam and other tests.

- Genetic counseling can help family members understand how genetic test results may affect them individually and as a family.

- Treatment for Alagille syndrome includes medications and therapies that increase the flow of bile from the liver, promote growth and development in infants' and children's bodies, correct nutritional deficiencies, and reduce the person's discomfort.

- Scientists have not yet found a way to prevent Alagille syndrome.

- Caregivers and parents of children with Alagille syndrome should try to maximize their children's potential for growth through good eating, diet, and nutrition.

[Top]

Clinical Trials

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for youExternal NIH Link.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at www.ClinicalTrials.govExternal Link Disclaimer.

This information may contain content about medications and, when taken as prescribed, the conditions they treat. When prepared, this content included the most current information available. For updates or for questions about any medications, contact the U.S. Food and Drug Administration toll-free at 1-888-INFO-FDA (1-888-463-6332) or visit www.fda.govExternal Link Disclaimer. Consult your health care provider for more information.

The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. Trade, proprietary, or company names appearing in this document are used only because they are considered necessary in the context of the information provided. If a product is not mentioned, the omission does not mean or imply that the product is unsatisfactory.

[Top]

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. The NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings through its clearinghouses and education programs to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by the NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank:

David A. Piccoli, M.D., The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; Binita M. Kamath, MBBChir., the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario

This information is not copyrighted. The NIDDK encourages people to share this content freely.

[Top]

September 2014